Can and Will

by Jon Beaupré

________________________

Can’t and Won’t

by Lydia Davis

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

© 2014 ISBN 2013033909

It is no surprise that we live in an age of minimalism. With Twitter oeuvres in 140 characters, a limited attention span, and an irresistible drive to get to the punch line, many of our most provocative and engaging works are created by layering simple story on top of simple

story. Immediately the work of Nicholson Baker comes to mind - Vox being just one of my favorites; a naughty book that gets to the point rather quickly, but nonetheless, traverses vast territory with its limited lines. There is a popular collection of very short stories, entitled appropriately, World’s Shortest Stories, all of which are 55 words, no more, no less. The discipline of fitting into the 55 word rubric, not unlike a Twitter novel, forces the writer to make his or her points pretty quickly. There is no space for wandering, unlike Proust’s Macaroon (or was it a Madeline?), taking fourteen pages to swoon over the subtle memories of a storied pastry. No, every word has to count, and if those words are suggestive and evocative of a larger reality, all the better, one small minimalist idea suggesting or implying a larger reality.

story. Immediately the work of Nicholson Baker comes to mind - Vox being just one of my favorites; a naughty book that gets to the point rather quickly, but nonetheless, traverses vast territory with its limited lines. There is a popular collection of very short stories, entitled appropriately, World’s Shortest Stories, all of which are 55 words, no more, no less. The discipline of fitting into the 55 word rubric, not unlike a Twitter novel, forces the writer to make his or her points pretty quickly. There is no space for wandering, unlike Proust’s Macaroon (or was it a Madeline?), taking fourteen pages to swoon over the subtle memories of a storied pastry. No, every word has to count, and if those words are suggestive and evocative of a larger reality, all the better, one small minimalist idea suggesting or implying a larger reality.

Minimalist doesn’t mean that the entire work is made of few words either. Luc Sante’s masterful collection of the 19th Century news filler pieces by the French writer Felix Fénéon entitled Novels in Three Lines are gorgeous for their evocative simplicity, but the collection feels endless, like eating handful after handful of popcorn; an undeniable pleasure. The great works of the composer Philip Glass are often lofty and hypnotic, vast meditations on - well, just about anything - but made up of microscopic changes in chord, mood, rhythm; hence minimalist despite their over all length.

That brings us to the rich treasure of new work by the novelist Lydia Davis, that consist of several dozen observations on what might appear to be of the trivial and irrelevant, but in her hands become little gems, masterpieces of invention and reflection. Early in the book she writes a short piece entitled The Dog Hair:

The dog is gone. We miss him. When the doorbell rings, no one barks. When we come home late, there is no one waiting for us. We still find his white hairs here and there around the house and on our clothes. We pick them up. We should throw them away. But they are all we have left of him. We don’t throw them away. We have a wild hope - if only we collect enough of them, we will be able to put the dog back together again.

That’s the whole piece. In fewer than ten sentences, we learn of loss, longing, domestic life lived by a couple, irrational hope, and the unexplainable bond between a dog and his human companions.

In fact, many of the short masterpieces of Lydia Davis are tinged with melancholy; not exactly tragedy, but a kind of sad boredom that leaves us wondering in our tracks ‘where is that story supposed to go?’

Davis, who was married for four years to the author Paul Auster, has been the recipient of a number of literary awards; something which undoubtedly pleases her but also leaves her pondering whether or not she deserved the award, or rather she should have gotten the award for another work, or she wonders why she didn’t win a more prestigious award. Frankly, she’s a little bored and cranky about it.

In April of this year on the recently cancelled NPR program Tell Me More, host Rachel Martin asked about this boredom. Davis replied:

Actually, I don't mean I'm bored by old novels and books of stories if they're good. Just new ones — good or bad. I feel like saying: Please spare me your imagination, I'm so tired of your vivid imagination, let someone else enjoy it. That's how I'm feeling these days, anyway, maybe it will pass

So along with the melancholy, there is a touch of opinionated and cranky curmudgeon. But the curmudgeon has a marvelous sense of observation and draws wicked conclusions from what she experiences. Even the ideas for the pieces - taken from dreams, verbatim snippets of Madame Bovary, and just plain off the wall, odd ideas - become hypnotic little gems, like a passage of Philip Glass, that you just want to let roll over you like a good idea.

I think my favorite sequence in the collection is the 15 page story

entitled The Cows which reports on the step by step progress of a group of cows during the course of a day. The account is detailed, accurate, and more anthropological journalism than fiction. (“ They are so black on the white snow and standing too close together that I don’t know if there are three there, together, or just two - but surely there are more than eight legs in the bunch…”) You get the impression that Ms. Davis is the opposite of cynical; there is nothing tongue in cheek in her 15 page report on the step by step behavior of this herd of cows; the report is detailed, filled with simple observations, and is ultimately seductive, because just as you realize that nothing special is going to happen with these cows - no denoument, nor climax to the story - you are too far into the story to pull away, asking yourself ‘why is she recounting the minute by minute behavior of a herd of cows, like Anderson Cooper in a Hurricane? The account is accurate (we assume), detailed, and consequential. But why cows? Apparently, Ms. Davis found the herd more interesting than any of its parts, but that you couldn’t describe the whole of the bovine hive without describing the behavior of the individual cows. I was reminded of a more literary Jane Goodall, bringing to our attention the fascinating behavior of a much more common species than the great apes of Africa. A minimalist fascination with a banal subject, raised to the level of an engaging, slightly cracked soap opera .

|

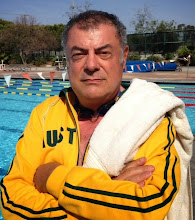

Lydia Davis

Independent.co.uk

|

After staying with the others in a tight clump for some time, one walks away by herself to the far corner of the field: at this moment she does seem to have a mind of her own.

I want to know why the cow walks to the other end of the field, but it may just be a mystery of cow reasoning and that’s all there is to it. Ms. Davis may be ever so slightly cranky, but she is also fanatically accurate in her observations and the combination of the two make the story, and the dozens of other little fragments like lovely little thought bombs that go off as you read them.

If only all the twitter messages I receive were so clever and pregnant with implication and meaning